Imagine a world where the price of gasoline fluctuates wildly, reaching astronomical highs during a summer heatwave or plummeting to rock-bottom levels when oil prices crash. This chaotic scenario highlights the need for mechanisms that can stabilize prices and prevent market volatility from impacting consumers and businesses alike. Enter price ceilings and price floors, government-imposed interventions that aim to regulate prices within a specific range.

Image: www.youtube.com

Price ceilings and floors are essentially legal limits placed on the maximum (ceiling) or minimum (floor) prices that can be charged for a good or service in a particular market. While they can seem like simple solutions for economic woes, these interventions can have complex and sometimes unintended consequences, particularly when they become “binding,” meaning they actually influence the market’s natural equilibrium. This article dives deep into the intricacies of binding price ceilings and floors, exploring their historical context, economic effects, and real-world examples.

Unveiling the History: Price Controls Through the Ages

The concept of price controls dates back centuries, with ancient civilizations utilizing them to address food shortages and ensure equitable distribution. For example, ancient Roman emperors implemented price ceilings on grain to prevent mass starvation during times of scarcity. Throughout history, price controls have been employed during wartime to stabilize prices, prevent profiteering, and ensure the availability of essential goods.

However, the 20th century witnessed a massive proliferation of price controls, particularly during periods of global economic turmoil, such as the Great Depression and World War II. In the 1970s, the United States grappled with the energy crisis and implemented price controls on oil and gasoline, aiming to curb inflation and protect consumers from exorbitant price increases. These policies, while well-intentioned, often led to unintended consequences, including shortages, black markets, and economic distortions.

Unpacking the Basics: Price Ceilings and Price Floors

A price ceiling is a legal maximum price that sellers can charge for a good or service. It’s like a ceiling on the price, preventing it from exceeding a certain level. A price floor, on the other hand, is a legal minimum price that buyers must pay for a good or service. It’s like a floor holding the price up, preventing it from falling below a certain level.

Binding Price Ceilings: Occur when the government sets the maximum price below the market equilibrium point, where supply and demand intersect. When a binding price ceiling is enforced, demand outstrips supply, creating a shortage. Consumers are eager to buy at the lower price, while producers are less willing to supply, resulting in a gap between what buyers want and what sellers are willing to offer.

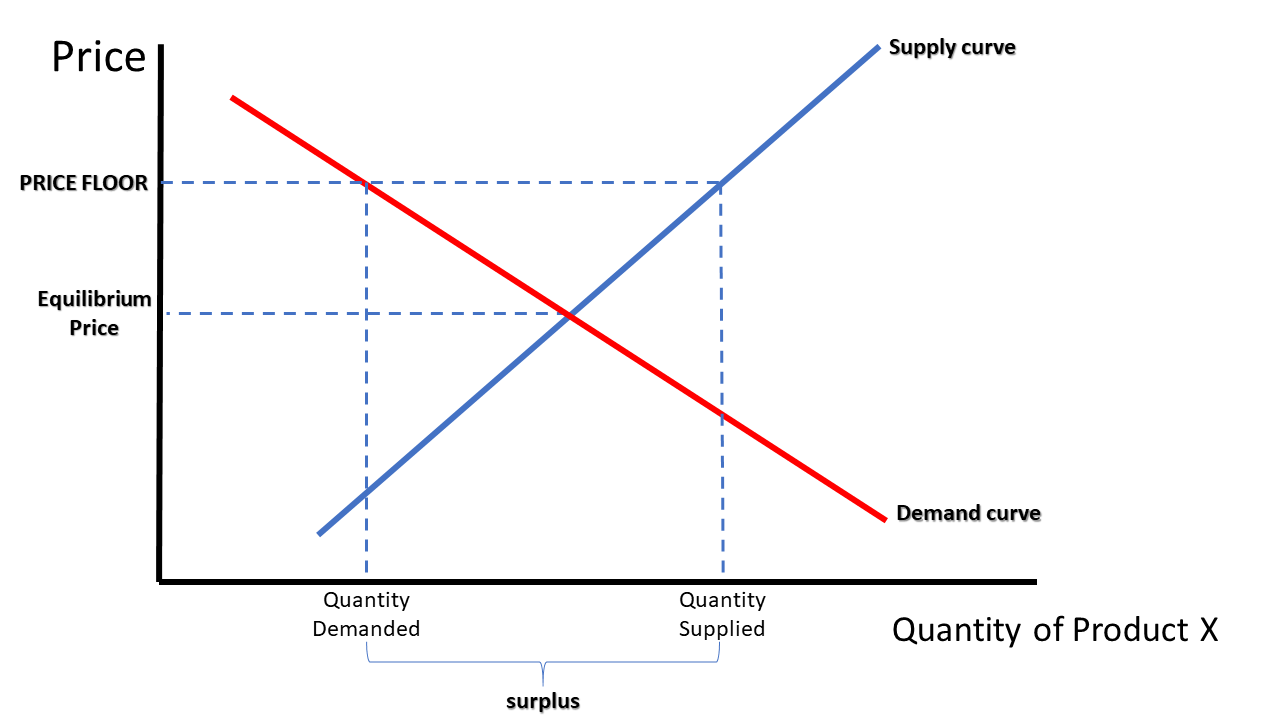

Binding Price Floors: Happen when the government establishes a minimum price above the equilibrium point. This intervention results in a surplus, as the mandated price discourages consumers from buying, while producers are incentivized to supply more at the higher price. The excess supply is left unsold, leading to a market imbalance.

Consequences of Binding Price Ceilings

While price ceilings can seem alluring, especially in times of rising prices or shortages, they are not without their drawbacks. Here are some key consequences of binding price ceilings:

-

Shortages: As we mentioned earlier, a binding price ceiling creates a gap between the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied. Consumers are willing to buy more at the lower price, but producers are less motivated to supply. This disparity leads to widespread shortages, leaving consumers frustrated and unable to obtain the goods they need.

-

Black Markets: When the official market cannot meet consumer demand due to price limitations, it can lead to the emergence of black markets. These illicit markets operate outside the regulatory framework, often with higher prices and less safety for consumers. Black markets can also contribute to corruption and undermine the legitimacy of official markets.

-

Reduced Quality: With limited profit margins, producers may be forced to cut corners on product quality to remain competitive under price ceilings. This can result in inferior goods or services for consumers.

-

Disincentive for Investment: Producers may be less likely to invest in production or innovation when they face price constraints. They may see limited returns on investment and opt for less profitable alternatives, hindering long-term economic growth.

-

Inefficient Allocation of Resources: Price ceilings can disrupt the efficient allocation of resources by influencing supply and demand patterns. If prices do not accurately reflect market forces, resources may be directed towards less productive uses, leading to economic inefficiency.

Image: www.gpb.org

Consequences of Binding Price Floors

Price floors can also lead to unintended consequences, particularly when they become binding. The minimum price mandated by the government can distort market forces and create challenges for both producers and consumers.

-

Surpluses: As mentioned earlier, price floors lead to surpluses because producers are willing to supply more at the higher price, while consumers are less willing to purchase at that level. This surplus of unsold goods can result in loss for producers, wasted resources, and inefficiency in the market.

-

Disincentive for Consumption: Price floors discourage consumers from purchasing goods or services because of the higher cost. This can lead to a decline in overall demand and market activity, impacting both producers and consumers.

-

Informal Markets: Similar to price ceilings, price floors can foster informal markets where goods are sold below the mandated minimum price. These informal markets can operate outside the regulatory framework and pose risks to both consumers and businesses.

-

Waste: When a price floor is set above the market equilibrium, producers are incentivized to produce more than what consumers are willing to buy. This surplus often leads to waste and lost resources, impacting economic efficiency and sustainability.

Illustrative Examples: Real-World Applications of Price Ceilings and Floors

To understand the real-world implications of binding price ceilings and price floors, we can look at some historical and contemporary examples:

-

Rent Control in New York City: New York City has a long history of rent control, which has sought to protect tenants from excessive rent increases. While it has provided some benefits for tenants, it has also contributed to housing shortages and disincentivized landlords from investing in property maintenance, leading to a decline in the overall quality of rental housing.

-

Minimum Wage Laws: Minimum wage laws are a form of price floor that aims to establish a minimum wage that employers must pay to workers. While intended to protect workers, minimum wage laws can lead to job losses, particularly for less skilled workers, as businesses may find it more profitable to employ fewer workers or adopt labor-saving technologies.

-

Agricultural Price Supports: Governments often implement price floors for agricultural commodities, such as wheat, corn, and soybeans, to protect farmers from volatile market conditions. However, these price supports can create surpluses, leading to government stockpiling and price distortions, potentially impacting consumer prices.

-

Price Gouging Laws: Some states have enacted laws to prevent “price gouging” during emergencies or disasters. These laws typically impose price ceilings on essential goods and services, aimed at preventing exorbitant price increases and protecting consumers from exploitation.

Expert Insights and Actionable Tips

The renowned economist Milton Friedman famously stated, “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Similarly, government interventions in the market, such as price ceilings and floors, are not without costs or trade-offs. While these policies may seem like simple solutions to complicated problems, they can often lead to unintended consequences that can outweigh the intended benefits.

Here are some key takeaways and actionable tips for navigating the complexities of price controls:

-

Consider the Long-Term Implications: Before enacting price ceilings or floors, carefully consider the potential long-term consequences for both producers and consumers. Evaluate the potential for shortages, surpluses, black markets, and unintended economic distortions.

-

Embrace Market Mechanisms: While government intervention may be necessary in certain circumstances, it’s crucial to recognize that market forces are often the most effective means of allocating resources efficiently. Encourage competition and allow prices to fluctuate freely to reflect supply and demand.

-

Transparency and Fairness: If government intervention is deemed necessary, ensure that policies are implemented transparently and fairly, considering the interests of all stakeholders. Provide clear guidelines for price restrictions and enforce them consistently to minimize regulatory uncertainty and market distortions.

-

Evaluate and Adapt: Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of price ceilings and floors and be prepared to adapt or adjust them based on changing market conditions and unforeseen consequences. A dynamic approach to price controls is essential for mitigating unintended outcomes and promoting market stability.

Price Ceilings And Price Floors That Are Binding

Conclusion

Price ceilings and price floors can be powerful tools for addressing specific market failures or achieving social goals. However, it’s essential to recognize the complexities of these interventions and their potential for unintended consequences. When these controls become binding, they can disrupt market dynamics, leading to shortages, surpluses, black markets, and inefficient resource allocation. When evaluating price control policies, it’s crucial to consider the long-term implications for both producers and consumers, embrace market mechanisms whenever possible, and strive for transparency and fairness in implementation. By understanding the intricacies of price ceilings and floors, we can make informed decisions that promote a more stable and equitable market for all.